A reflection on co-produced research with young people by PhD student Charlotte Webber as she begins a project seeking to tackle the drop-off in young people’s reading motivation.

Having a background in research and beginning a PhD programme aiming to understand young people’s reading experiences, I was anticipating that my project would require me to recruit some young people as participants. I expected that I would work with my participants mostly during the data collection stage, doing most of the project planning and analysis on my own. However, as I began reading around the topic, I realised that much research in the field of reading and literacy has already been done in this way– coming up with hypotheses, testing and/or giving out questionnaires to students and analysing their answers. Despite this, we are no closer to understanding why young people are choosing to read less and less as they get older.

What struck me as I began thinking about the methods I wanted to use for my project was that very few studies exploring young people’s reading experiences have collaborated with the students they were studying.

%20(1).jpg)

Even studies using qualitative approaches (e.g., interviews) have mainly interpreted young people’s answers from an adult perspective. Very few studies, if any, appeared to work alongside young people to develop research questions, plan data collection or interpret the findings. This means that the picture that has been built up of young people’s reading experiences fails to include the voices of young people themselves. As adults, we can develop all sorts of hypotheses as to why young people might be disinclined to read for pleasure – preference for social media, increased pressures at school, lack of access to relevant books – but without including young people in the discussion, we will never truly understand how reading fits (or doesn’t fit) into their lives. This is what led me to co-production work.

One of the key points of emphasis within co-production work is that communities are experts in their own lives. For young people, this seems especially relevant. Our teenage years are filled with change (e.g., moving from Primary to Secondary school, changing friendship groups and more time spent away from parents). There is also an increasing workload in school, not to mention additional social pressures to contend with. Though I still like to consider myself a relatively young person (though I am now much closer to 30 than I am to 16), I am aware that young people’s worlds are vastly different from my own. They’re also vastly different from how my life was even when I was in Secondary school; when I was 16, social media was only just developing, exams didn’t feel future-defining and my parents plied me with YA fiction – the world certainly looks a lot different now. With all this in mind, to try to conduct research about young people today and make assumptions about their lives without including them in the process seems insufficient.

For my project, the first step on this path is to convene a panel of young people to work alongside the (adult) research team to create research questions and develop methods of collecting data which will truly centre young people’s voices as the project evolves. We’ll discuss what ‘counts’ as reading in an increasingly digital world, how we could talk to young people about their reading experiences and what is needed to make reading for pleasure more accessible and/or appealing for young people. At the outset, as with all co-production work, there are a number of issues that need consideration.

For example:

(1) Power: Even though co-production aims to reduce the power imbalance between the researcher and the researched, I have found myself questioning whether it is possible for everyone to have equal power in a project where adult team members have more academic qualifications, higher salaries and more research experience than the younger team members. Furthermore, ‘inviting’ young people to become collaborators after the project had already started meant that some decisions had already been made without their input(e.g., how many students should be part of the panel and where we should recruit them from).

(2) Consent: Where I am hoping the project will evolve as it proceeds, I am aware that it may be unclear at the start how much time young people should expect to commit or what the exact duties of each team member will be, making it hard to be upfront about what panel members are consenting to.

(3) Payment: Some young people might feel that payment creates expectations about how much they need to commit to the project, while others might feel that is makes their contributions feel valued. Payment decisions also speak to the issue of power; if young people think they are being ‘employed’ by adult members of the team, they may feel less comfortable challenging their opinions or decisions.

Having an open and honest discussions with the panel about these things at the outset means that, hopefully, everyone can contribute to the project in ways that feel meaningful for them and which value their contributions. This means that our first meeting will likely contain a lot of ‘housekeeping’, but I consider these conversations vital in creating an equitable and lasting relationship from the start.

Co-production is often described as ‘messy’, and things will need to be readjusted, reflected upon and re-evaluated throughout. However, particularly when co-producing with young people, this is where the greatest value lies.

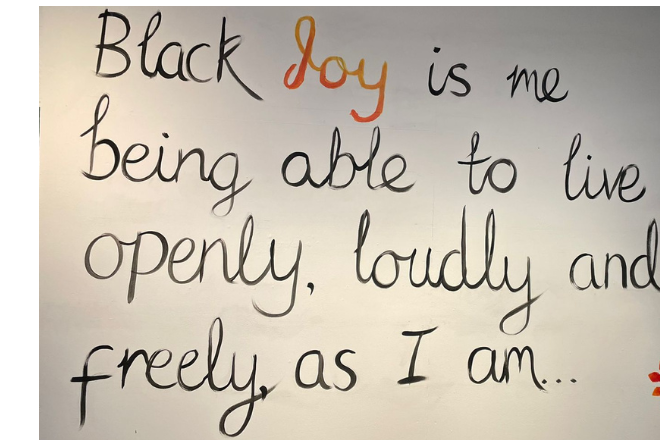

Young people contribute creative ideas and bring perspectives which are often radically different from those of adult team members. I for one am intrigued to find out how young people think about reading today, and how we should study it, and am hopeful that their insights will lead to a reimagining of our understanding of their reading experiences that would not have otherwise been possible.

Author biography: Charlotte Webber is a PhD Candidate working with Scottish Book Trust and University of Edinburgh on projects to support reading motivation in young people. She believes that collaborating with young people and connecting academic research with real-life experience is essential for understanding how to make meaningful change and aims to use co-production principles and practices to achieve this.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)