A co-producer shares their experience of being Clinically Extremely Vulnerable – and the lack of support this community is receiving.

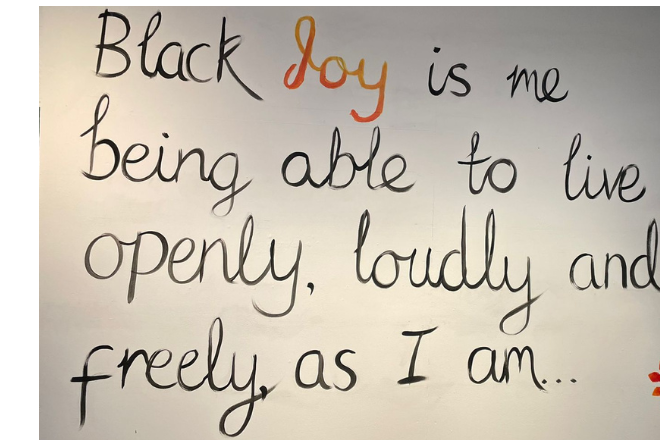

Last week was my two-year anniversary of not going into a shop, apart from to collect prescriptions. Two years of not eating a meal out, of choosing a birthday card for someone, of, well, of… anything. The only human hand I’ve felt on mine in two years is that of a doctor or nurse.

I’m lucky. I’ve twice lost all my work and income and have permanently lost my pension scheme contributions. The first time was when I became unwell suddenly five years ago and the second when the pandemic hit, four weeks after I had just started to work again. I’m still lucky. I have been able to keep safe because I have a job that I can do from home – for now. I’ve gradually built up my health with help from all my medical teams and approval for funding for an expensive, rationed drug. I can work part time if I pace my energy carefully. I still can’t go anywhere where there are other people, such as into shops or the cinema, because I’m in the Clinically Extremely Vulnerable (CEV) COVID-19 group. I say group, but the CEV population is more like the size of a city.

Uncertainty and contradictions

There are 3.8million CEV people in England, and more across the whole of the UK. That is a huge number of people pretty much confined to keeping away from others if they want to stay as well as they can. The government has abolished the help it gave at first to those in the ‘shielding’ group, has removed nationwide precautions and restrictions and financial and practical assistance, and has not quite mentioned that the CEV people are still advised to take extra care. I am in the lucky group on a hospital list. I have a number to ring if I test positive for COVID-19 using my special red ‘priority’ PCR test. If I remain lucky after further analysis of my details, anti-viral medication is couriered over to me. I feel truly lucky that I am in that group. Some people I know who are even more clinically vulnerable than I am are in a part of the country which has not been able to organise itself as well as where I live and they have no priority red box, no phone number to call and no information about their eligibility to have anti-virals.

There is a contradiction here. Medical charities are campaigning hard to address this but more needs to be said, and heard. If COVID-19 post vaccination poses so little risk to CEV people that they no longer need to ‘shield’ why are the guidelines still in place? Why do we have our little red priority PCR test boxes? Not much has been said about the Octave study whose data published in August 2021 showed that a significant proportion of immunosuppressed people do not mount an adequate response to theCOVID-19 vaccinations. I have had four vaccinations and I am lucky and grateful to have had them, but I have no idea if they offer me protection from serious effects from the virus. There has recently been an announcement that Evusheld has been approved as a prophylactic treatment for the most vulnerable. Wouldn’t that be wonderful, to have a preventative drug that would mean I could go out, see friends and family properly, choose presents and cards in shops, buy less expensive food in supermarkets, and have a choice of whether one day I could once again work in the places I’ve trained for many years to practise? There is a slight caveat, though. I can’t see in the Evusheld announcement any information about who might receive it and when it might be available. Still, small glimmers of hope are not to be dismissed.

What lies ahead?

I have to tell myself that I’m lucky or the reality of the unknown stretching out ahead hits home. I’m lucky I can keep busy with work when I’m well enough to do it. I’m lucky that I have a fantastic family who have restricted what they do so that they can see me at a distance on special occasions and who have stepped in to offer financial help when I could have lost my home.

I’m lucky that one particular individual gave me a chance to work again, on a voluntary basis at first when the pandemic started, and then for two days a week. I’m lucky that some other colleagues were not put off by the fact I’d been ill and invited me to work for another day a week. I’m lucky that I have had the training and education to allow me to try to find other ways of working. I will always be grateful for those, but I have no idea whether the work I have now will continue and whether the working from home concept will continue to be tolerated.

What if nothing works in the long-term management of CEV people, and what if nothing changes? My choice is to go out where there are other people and risk my health, having already been significantly unwell to the point of having had multiple hospital admissions, numerous powerful drugs and having lost my whole professional world and all income once already. Alternatively, my choice is to stay at home being lucky, with an unknown length of solitude stretching before me.

I am lucky. I have that choice. Those whose work means they have to go out to risky environments to earn money, those who need to try to keep their children’s lives as normal as possible by taking them to school, making sure they can see their friends and take part in all the activities a child’s life should have, and those who are even more unwell or at higher risk than I am don’t have that choice.

There are many things I want to do, dream of doing again or for the first time. I’m not ready to stop living my life, but I have to suppress those daydreams or I stop feeling lucky.

Today I noticed that the government website states ‘people are no longer being called extremely vulnerable’. Am I now like the Artist Formerly Known as Prince, in that I am now to be referred to as PPKCEV, Person Previously Known As Clinically Extremely Vulnerable. I think the government might be disappointed to discover that removing an acronym does not make an entire group of people disappear. The government of the UK needs to remember there is a city of people out there they no longer seem to be holding in mind. Even the letters from the government saying they recognise we have a different life to everyone else have stopped. They made a difference. It would be so easy to send some more – but that would mean recognising, listening to and working with the CEV people.

Support and advice

Mind - Coronavirus and your wellbeing

National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) - Taking care of your mental wellbeing

Kidney Care UK - Coronavirus (Covid-19) guidance for people with kidney disease

NHS South Tees - How am I? tool to support psychological health and The Coronacoaster videos to support management of the pandemic's emotional rollercoaster

NHS - Your COVID recovery

Further reading

Kidney Care UK - Charities urge PM to support over 500,000 immunocompromised people to live alongside Covid-19

Health Foundation - Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on the clinically extremely vulnerable population

BMJ - Covid-19: For the clinically extremely vulnerable, life hasn’t returned to normal

BMJ - We need to talk about shielders

Department of Health and Social Care - Guidance for people previously considered clinically extremely vulnerable from COVID-19

Kings Fund - Why didn't the Covid-19 vaccination work for immunocompromised people?

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)